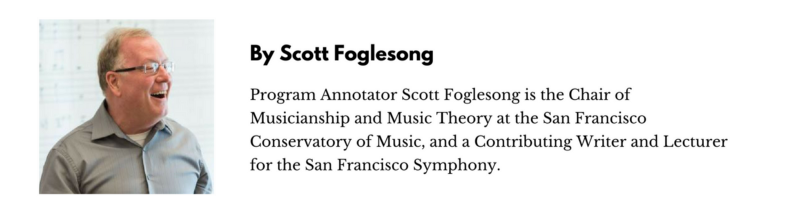

Ludwig van Beethoven – Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus (1801)

Portrait of Beethoven by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1820 (pictured left) and Prometheus depicted in a sculpture by Nicolas-Sébastien Adam, 1762 (pictured right).

We tend not to think of Beethoven as a theatrical composer. We think symphonies, we think sonatas, we think string quartets and piano trios and concertos. After all, he wrote only one opera (Fidelio) plus a smattering of incidental music.

And there’s a ballet: The Creatures of Prometheus, written for the Vienna Court Theater. We don’t know very much about the production. What we have is an overture, an introduction, fifteen dance numbers, and a finale, written about the same time as Beethoven’s first symphony.

The Overture is a jim-dandy bit of orchestral magic that opens with a resounding wallop and continues to a passage of dignified nobility, then erupts into high-spirited muscularity. Beethoven packed a lot of music into the overture’s approximately five minutes.

Nota bene: one of the Prometheus dance numbers is a modest little contredanse that went on to great things: Beethoven re-purposed it for the finale of the Eroica symphony, in which he cultivated that modest nugget of a tune into a towering edifice of Western music.

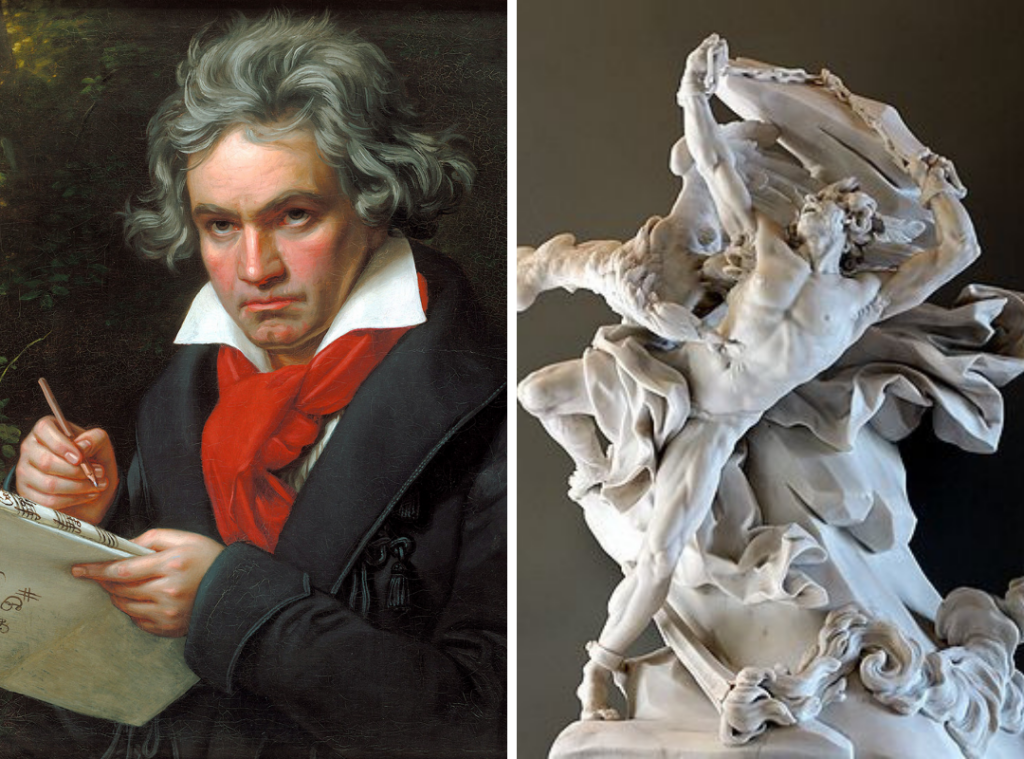

Gabriela Lena Frank – La Centinela la Paloma (2010)

Composer Gabriela Lena Frank (pictured left) and Artist Frida Kahlo (pictured right).

Perhaps there are other disciplines that I could have aimed my life at — I seriously considered political science and law — and who knows where those roads would have led? But my sense of self has developed inexorably along the simple principle of storytelling and creating objects of beauty through sound, leaving the earth hopefully a bit better.

Thus Gabriela Lena Frank, a notably successful practitioner of a profession not particularly noted for successes. Her influences and inspirations reach far beyond her native Berkeley, including Latin America (Peru in particular), Asia, and Eastern Europe. Frank tells us that La Centinela y la Paloma (The Keeper and the Dove) “finds its inspiration in two national treasures of Mexico: its annual Día de los muertos (Day of the Dead) folk-Catholic festival and iconic painter Frida Kahlo.” A cycle of four songs, the work “features two characters: Catrina, the keeper of souls (also known as the Lady of Death), who bestows a gift but once a year to the spirits in her charge whereby they can visit their loved ones still living; and Frida, who, having predeceased her beloved husband Diego Rivera, yearns to see him once again.”

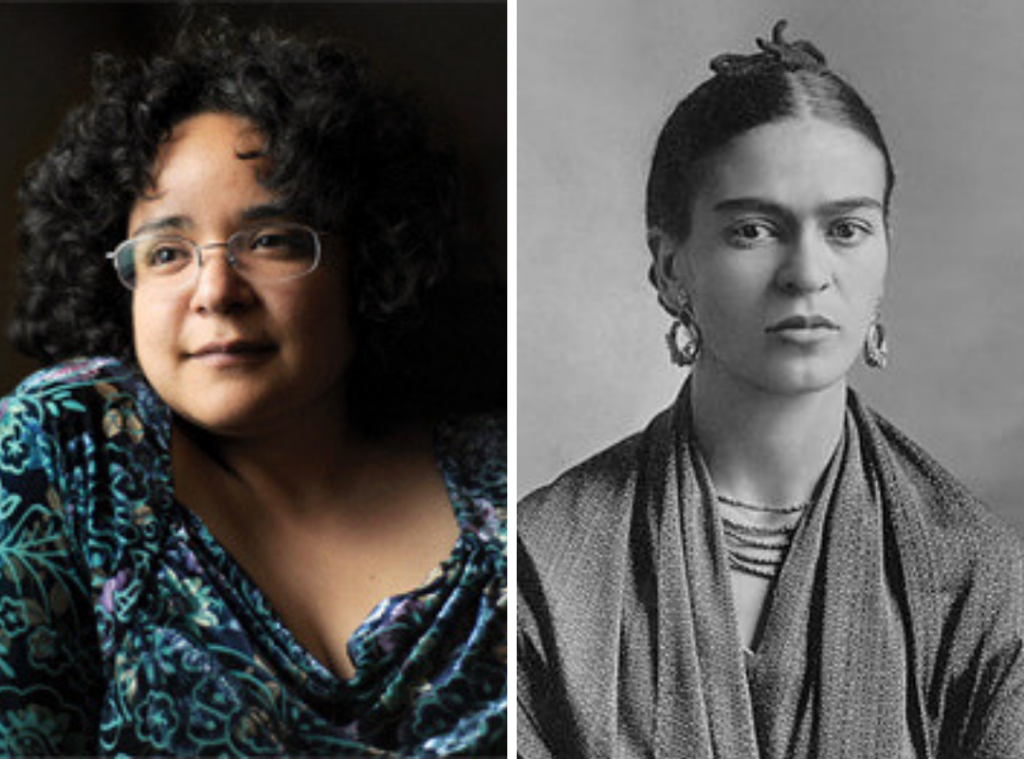

Gustav Mahler – Lieder (2010)

Composer Gustav Mahler (pictured left) and Poet Friedrich Rückert (pictured right).

Art songs (lieder in German) play a surprisingly large role in the output of a composer who is generally associated with matters symphonic. Mahler was fundamentally a lyrical composer who thought in terms of vocal lines; while he sometimes included his lieder in his gigantic symphonies, those songs stand perfectly well on their own merits.

Mahler usually grouped his songs into thematically-related collections, one of which is Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn), its texts taken from an early 19th century collection of poems that celebrated an idealized Germanic folklore. In “Rheinlegendchen” (Little Rhine Legend) we hear the fancy of a youth who bewails his sweetheart’s fickleness yet hopes for reconciliation. Yet another lovesick swain speaks of his yearning for the innkeeper’s daughter in “Wer hat den das schöne Liedlein erdacht?” (Who has thought up this pretty little song?)

Mahler’s songs on texts by Friedrich Rückert stand amongst his most intensely-felt vocal works. “Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder!” (Look not into my songs) speaks of simply enjoying the fruits of creative work rather than looking too closely at the process, while “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen” (I am lost to the world) belongs amongst Mahler’s most personal utterances, a portrait of a solitary figure in withdrawal from the world and all its ills.

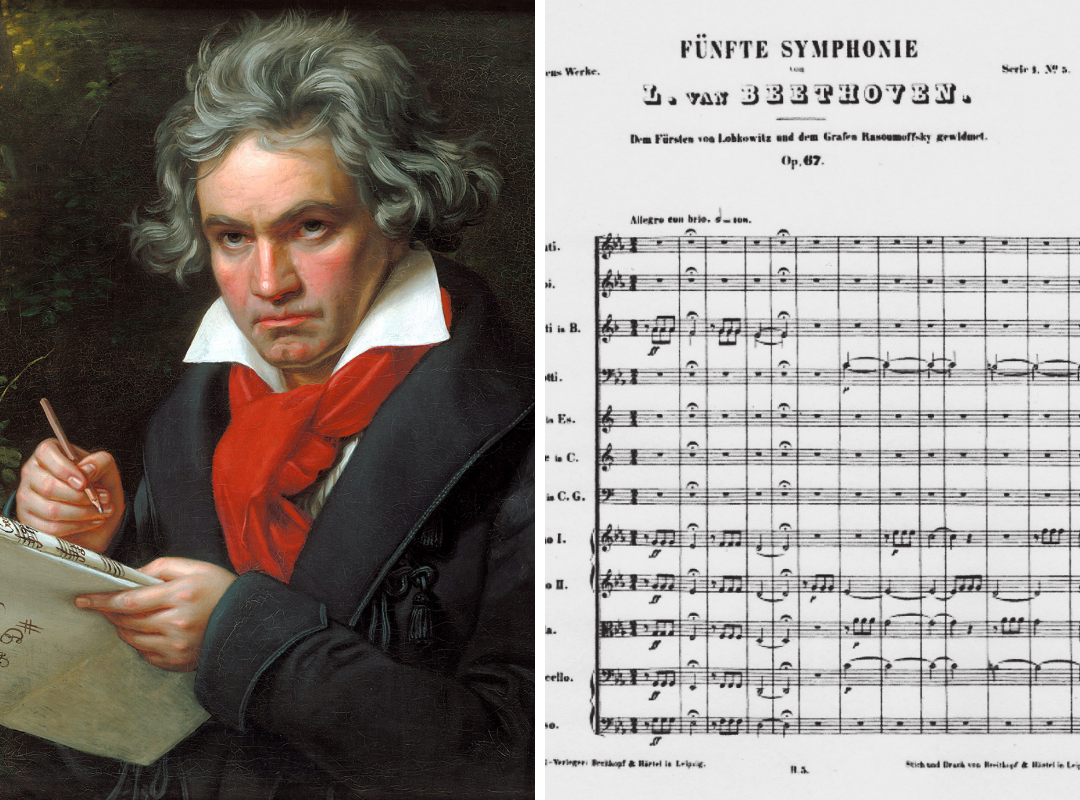

Ludwig van Beethoven – Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 6 (1808)

Portrait of Beethoven by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1820 (pictured left) and a score of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

Beethoven’s Fifth was introduced to the world on a maiden voyage so trouble-plagued as to have scuttled a lesser work. The date was December 22, 1808. The venue was Vienna’s Theater an der Wien. The concert was a mess. Most of Vienna’s best musicians were working across town at a birthday bash for Joseph Haydn, leaving Beethoven with a B-list orchestra that struggled to get through a daunting program on a single rehearsal. The last-minute substitute soprano bungled her aria. Beethoven’s contradictory cues caused a major pile-up during the concluding Choral Fantasy. The theater’s heating system was on the fritz. The dismal (and frigid) evening dragged on for a good four hours. Some stalwart fans shivered through to the end, but most folks slipped out early.

And yet the music introduced on that elephantine scramble of a concert featured some of Beethoven’s noblest inspirations: both the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, the Choral Fantasy, the Fourth Piano Concerto, and the first Vienna hearings of the aria Ah, perfido! together with three sections of the Mass in C. Beethoven even threw in one of his legendary improvisations.

Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67 opened the second half of the concert. One can only wonder what it was like to hear those famous first four notes without any associations engendered by two centuries of familiarity. The muscular, almost impossibly compressed first movement surges forth: filled with turbulence, power, and conflict, it is not so much a musical statement as it is the opening salvo of a spellbinding oration.

The expansive and leisurely second movement might seem to counterbalance matters, but that’s not really the case: Beethoven throws in a loud reference to the first movement’s ta-ta-ta-Taa opening rhythm that establishes an ongoing journey rather than a digression. Then, in the co-joined third and fourth movements, Beethoven reveals the underlying psychological engine that powers this symphony’s unprecedented drama. The brooding menace of the third movement dissolves into a breathless stasis that evokes Thomas Merton’s ‘dark night of the soul’, followed by an overpowering surge in which existential angst gives way to triumph, its blazing optimism as inspiring today as it was 211 years ago on that icy Vienna premiere.

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the ground-breaking new music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

ICONIC BEETHOVEN takes place on Saturday, September 14 at 8 PM and Sunday, September 15 at 4 PM at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek. Tickets start at $42 / $20 for students 25 and under with valid Student I.D. and can be purchased online or by calling the Lesher Center Box Office at 925.943.7469.