Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Symphony No. 1 in E-flat Major, K. 16 (1764)

The Mozart family on tour: Leopold, Wolfgang, and Nannerl. Watercolor by Carmontelle, ca. 1763

A child prodigy of staggering talent, itty-bitty Wolfgang Mozart was trundled about Western Europe from ages 7 through 10 by his doting—and exploitative—father. The family arrived in London in April 1764, where eight-year-old Wolfgang formed a close bond with Johann Christian Bach, youngest son of the glorious Johann Sebastian and a leading exponent of the new Viennese Classical style. Christian took the brilliant youngster under his wing, and it was under his influence that Wolfgang wrote his very first symphony.

Nobody should expect to hear blazing originality in Mozart’s first symphony. He was a just wee lad, after all. And yet there’s nothing childish about the symphony; it comes off as the work of a competent adult. It partakes of the so-called Galant style—a music of elegance, sophistication, and not much drama. Sometimes derided nowadays as musical wallpaper, galanterie definitely has its place in the scheme of things. It is the music of a society that aspires to sand off its rough edges, to create a harmonious culture through meticulous etiquette. Consider the canvases of Watteau and Fragonard, with their visions of an idealized human society. Galant music reflects that yen for the ideal, and if it’s perhaps a bit too pretty for our grittier modern tastes, there’s something to be said for its gentle optimism.

Symphony No. 1 in E-flat Major, K. 16 demonstrates that Wolfgang was already well versed in symphonic forms and orchestration. To be sure, the manuscript contains annotations and corrections by Wolfgang’s father Leopold. The kid still needed coaching. But all in all, it’s nothing short of a miracle, a worthy first effort from a cute little squirt who was destined to become one of the greatest symphonists of them all.

Kevin Puts (b. 1972) – Flute Concerto (2013)

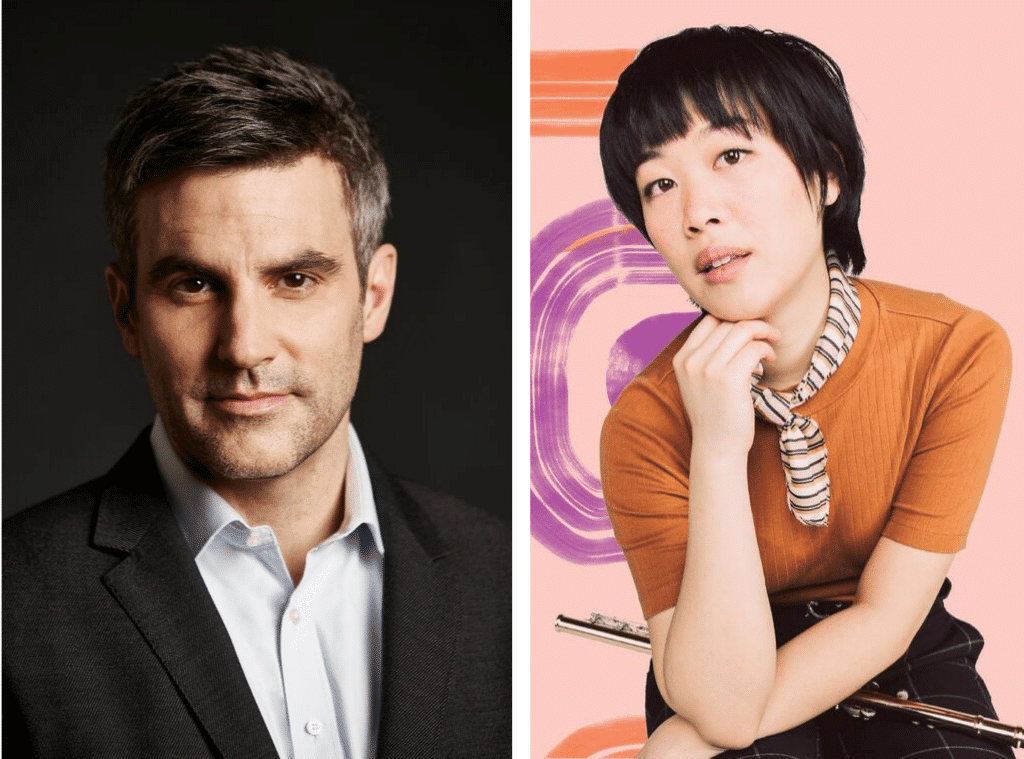

Kevin Puts, composer (pictured left) | Annie Wu, flute soloist on Puts’ Flute Concerto (2013) (pictured right)

Committed patrons are among the most powerful engines of musical development. Whether a wealthy heiress such as the Princess de Poliganc, née Winnaretta Singer of sewing-machine fortune, who commissioned works from Stravinsky, Satie, Milhaud, and others, or Hapsburg Imperial Librarian Gottfried van Swieten, who so influenced Mozart, Haydn, and the young Beethoven, passionate music lovers have provided the seed for any number of worthy compositions. We owe them all a big shout-out for their untiring zeal and generosity.

Thus Bette and Joe Hirsch and their long-standing relationship with the Cabrillo Festival in Santa Cruz, California. Both Bette and Joe were considering commissions from composer Kevin Puts, 2012 Pulitzer Prize winner and former Composer-in-Residence of the California Symphony. Eventually, it was decided to combine both potential commissions into a single work. Thus was born Kevin Puts’s Flute Concerto, premiered in August 2013 at the Cabrillo Festival.

For a composer, nothing is ever wasted. “What opens the concerto is a melody I have had swimming around in my head for more than half a lifetime now.” And memory extends even further: “The second movement was written during a period in which I was rather obsessed with the second movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto K. 467, often referred to as the ‘Elvira Madigan concerto’ due to its use in the eponymously titled film of the ’70s. What Mozart could evoke … is mind-boggling and humbling to me. Nonetheless, I decided to enter into this hallowed environment, and, in a sense, to speak from within it in my own voice.”

Integration and unification are always good practices, as in the rhythmically-charged final movement that takes its main materials from the first movement.

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) – Symphony No. 104 in D Major “London” (1795)

Portrait of Joseph Haydn by Thomas Hardy (1791)

To clarify: Joseph Haydn didn’t invent the symphony, but without question he is its presiding angel. And Haydn wrote a lot of symphonies—about 107 all told. Getting to know them all is a daunting challenge, but there’s not a dud in the bunch. Most of his earlier symphonies are relatively lightweight affairs, but by the 1780s Haydn had amplified the genre into unprecedented expressivity, scope, and depth.

The initial impetus of Haydn’s twelve “London” symphonies was the 1790 death of Nikolaus Esterházy, Haydn’s music-loving aristocratic employer since the 1760s. Nikolaus’s successor dissolved the court’s lavish musical kapell, although he kept Haydn on the books. Haydn, then 58 years old, could easily have slipped into a comfortable retirement thanks to a generous pension, but instead, he opted for two extended visits to London, where his music was revered.

The English public made Haydn rich. They also inspired him to write a bevy of glorious late works, in particular, the twelve “London” symphonies, which conclude with No. 104 in D Major, Haydn’s swan song to the genre he had done so much to establish and nurture. Everything about it teems with the irrepressible vitality and technical wizardry of this peerless musical craftsman. Nor were its manifold virtues lost on his English audience. Haydn wrote in his diary: On 4th May 1795, I gave my benefit concert in the Haymarket Theater. [I presented] a new Symphony in D, the twelfth and last of the English. … I made four thousand Gulden on this evening. Such a thing is only possible in England.

Haydn could have stayed in England permanently, but he opted to return home to Vienna in 1795. Over the next decade, he gifted posterity with the two oratorios The Creation and The Seasons, his final series of masses, his late string quartets, and even the superb Austrian (now German) national anthem. But he never wrote another symphony. Perhaps he knew that it was time to pass on the torch to younger creators such as Beethoven, who had written the first six of his nine epochal symphonies by the time Haydn went to his rest in 1809, honored and celebrated for a lifetime of superlative musical achievement.

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the California Symphony’s ground-breaking music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

MOZART AND HIS MENTOR takes place on Saturday, November 16th at 8 PM and Sunday, November 17th at 4 PM at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek. Tickets start at $42 / $20 for students 25 and under with valid Student I.D. and can be purchased online or by calling the Lesher Center Box Office at 925.943.7469.