Brahms and the Orchestra

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

It has been said that Brahms was an indifferent or unimaginative orchestrator. However, it has also been said that the bathtub was invented in Philadelphia in 1842, so let’s not believe everything we hear. Bathtubs date back thousands of years; Johannes Brahms was a wonderful orchestrator, imaginative, creative, and insightful.

That bromide about Brahms arises from the distinction between fancy orchestration and good orchestration. Composers such as Berlioz, Liszt, and Wagner made extraordinary use of large, varied orchestras, but their skill does not reside in their use of, say, military drums or speciallydesigned tubas. It’s how they use those instruments, and to what purposes.

It’s the ‘how’ by which Brahms reveals his utter mastery of the orchestra. He rarely employs anything but standard orchestral instruments, but that employment is extraordinary. Don’t listen for bling—there isn’t any. Listen for detail, for delicate and subtle blends of sound. Brahms’s orchestra is his own, unique creation—not in its physical makeup, but in its unmistakable sonority, variety, and richness.

Hungarian Dances Nos. 5 and 6 (arr. Parlow) (1879/1885 and 1868)

They may be relative lightweights amongst Brahms output, but the twenty-one Hungarian Dances from 1879 were not only his most popular compositions, but also his most profitable.

Originally for piano duet, they abound in a smorgasbord of orchestrations, including Hungarian Dances Nos. 5 and 6 by the otherwise obscure Albert Parlow, music director for the Prussian Army. Not only do both dances team with lively energy and robust spirits, but No. 5, inspired by the folk dance czardas, is one of Brahms’ most familiar works.

Symphony No. 3 in F Major, Op. 90 (1883)

By the middle of the nineteenth century the symphony seemed to be all but defunct as a living, breathing genre. Heralds had been proclaiming its passing for decades and audiences had accepted the situation as given. It all came down to the impact of Beethoven’s nine symphonies, considered as the peak achievements of the rapidly-coalescing ‘standard repertory’ and its roster of ‘great composers.’

Potential symphonists entering the field as of the 1850s had Beethoven’s legacy to contend with, and many turned their attention elsewhere, focusing on highly programmatic ‘symphonic poems’ or on hybrid oratorio-symphonies that blended operatic elements with symphonic textures. Those few who attempted actual, traditional symphonies tended to be conservative types who eked out derivative stuff that soon faded.

Brahms was at first reluctant to try his luck at such an apparently no-win challenge, but pressure on him as the chosen savior of the ailing genre increased steadily along with his growing reputation as a Beethoven-class structuralist.

It wasn’t until 1876—he was forty-three years old—that he finally produced his Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68, a majestic creation that proved that the symphony was by no means a spent force. He followed up quickly with a second symphony in D Major the next year, but held off from writing another symphony for another six years. In the meantime he busied himself with a string of consummate masterpieces—the Violin Concerto, Piano Concerto No. 2, and the two beloved orchestral overtures, Tragic and Academic Festival.

Symphony No. 3 in F Major, Op. 90 of 1883 is an extended essay in ambiguity. Both its musical and philosophical themes are set forth in the opening three notes, representing Frei aber fröh (Free, but happy), Brahms’ adaptation of Frei aber einsam (Free, but lonely), the personal motto of his close friend and colleague Joseph Joachim.

That motto runs throughout the symphony, its unsettled quality left unresolved until the very end of the symphony, when it is heard in a serenely unruffled guise that seems like a blessing or benediction. Along the way, high drama (first movement), touching intimacy (second movement), lyrical rapture (third movement), and even more intense drama (fourth movement, at least for a while), carve out a memorable journey that fully warrants Eduard Hanslick’s verdict as Brahms’ “artistically most nearly perfect” symphony.

Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 (1887)

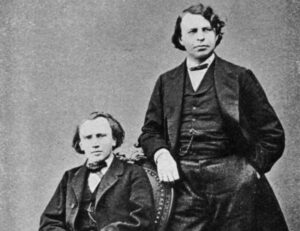

Johannes Brahms (left) and Joseph Joachim (right) c. 1855.

Given his general distaste for bling, Brahms was borderline aversive to the concerto genre, so often a sugary, empty-calorie affair stuffed with pointless display. By his late career he had written only three concertos, two for piano that were slow to achieve public acceptance, and a magisterial violin concerto for his friend Joseph Joachim that may be one of the supreme masterworks of the genre but had met with mixed reactions from critics and performers.

During the 1880s Brahms and Joachim had suffered through a deep rift in their relationship, engendered by Brahms’ appearing to side with Joachim’s wife Amalie during their divorce proceedings. The “Double” Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 can be understood as a peace offering of sorts, written specifically for Joachim and cellist Robert Hausmann. Like the Third Symphony, the Double Concerto employs a version of the “motto” theme Frei aber einsam (Free, but lonely) that Brahms associated with Joachim, and the work’s overall gestalt savors of that symphony’s tantalizingly elusive nature. It has always been a connoisseur’s concerto, deeply beloved by those who have become entranced by its subtle spell.

As one might expect, the Brahms Double Concerto is essentially a symphony with prominent solo parts for violin and cello. A magisterial first movement, in which a long orchestral introduction establishes the materials to be explored once the soloists enter, is followed by a meltingly beautiful Andante second movement, distinguished by the pristine sonority of the soloists playing in unison. A wonderfully neither-fish-nor-fowl finale never quite seems to make up its mind whether it’s a big finish or a sober exploration of a deceptively simple descending theme, before ending in a robust concluding gesture.

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the California Symphony’s ground-breaking music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

BRAHMS FEST takes place on Saturday, February 1 at 8 PM and Sunday, February 2 at 4 PM at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek. Tickets start at $44 / $20 for students 25 and under with valid Student I.D. and can be purchased online or by calling the Lesher Center Box Office at 925.943.7469.