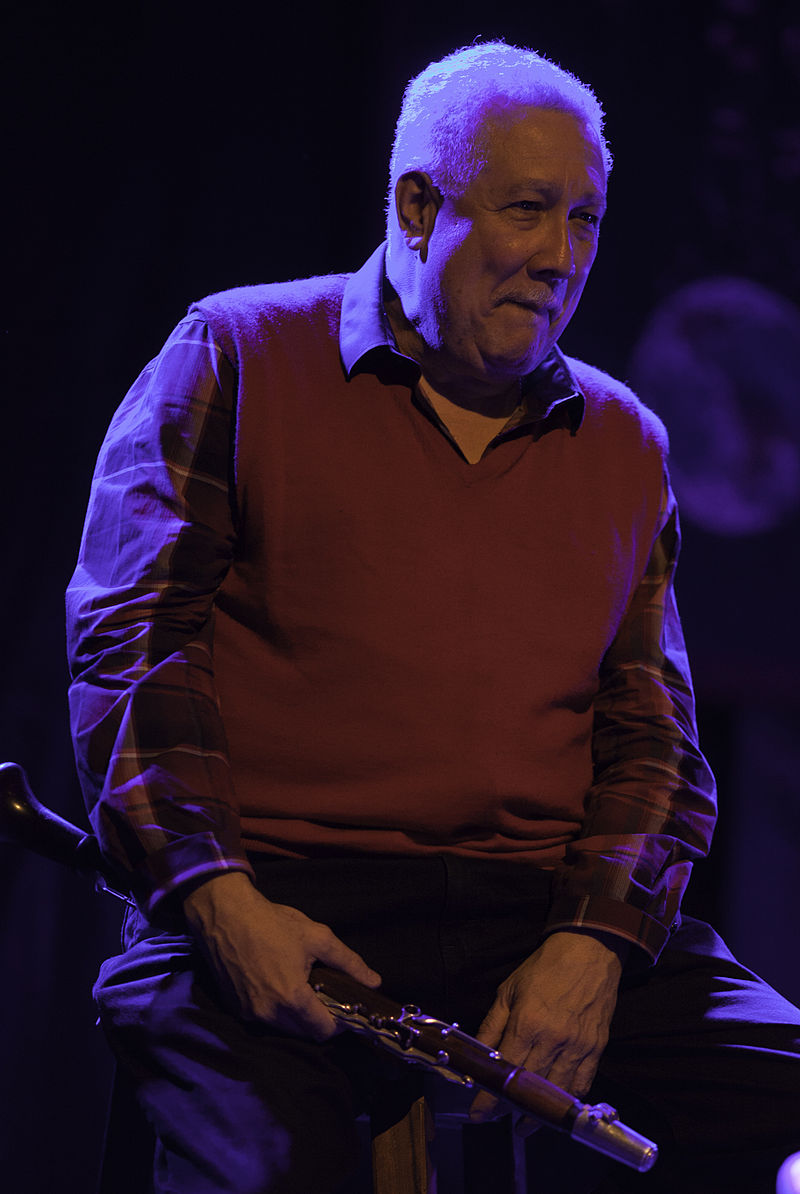

Paquito D’Rivera (b. 1948)

Aires Tropicales (1994)

D’Rivera onstage in 2013.

After Paquito D’River performed a dazzling jazz-inflected rendition of the Fantaisie-Impromptu on clarinet with combo backup, he pointed out to his Kennedy Center audience that the Fantaisie is the work of that esteemed Puerto Rican composer, Frédéric Chopin—who hails from the Caribbean side of Poland.

It was charming, funny, and witty. But more to the point, it reflected D’Rivera’s sheer comfort with performing, with making music, with being in front of an audience, in short, with himself. This multi-honored artist, a fourteen-time Grammy winner, who dwells happily (and comfortably) in the highest reaches of the profession, erases any artificial distinctions that one might be tempted to make regarding ‘classical’ or ‘jazz’ or ‘fusion’ or ‘crossover.’ None of those pat little labels have much meaning in regards to an all-encompassing musician such as Paquito D’Rivera, if in fact they can ever be said to have much meaning at all.

Born in Havana, he began studying the saxophone at the age of five and by the early 1970s had founded the remarkable group Irakere, which fused jazz, rock, classical, and native Cuban idioms. In 1980 he defected from Cuba and arrived in the United States, where his career has flourished. In addition to his prolific performing career in jazz and Cuban music, he is a noted composer with an enviable catalog of works commissioned by leading institutions worldwide.

Aires Tropicales dates from 1994 and was commissioned by the Aspen Wind Quintet; the premiere took place in New York City. Each of its seven movements stands alone as a complete composition that, according to the published program notes, “works well for jobs or educational concerts.” In this performance, the lively Venezuelan waltz Vals Venezolano is followed by a Ravel-inspired Habanero, concluding with the energetic Cuban dance Contradanza. The scoring requires a certain dexterity on the part of the performers: the flute doubles on piccolo with optional alto flute, and the oboe doubles on English horn. (The clarinet, horn, and bassoon players are not obliged to bring any other instruments to the concert, however.)

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Prelude from Partita No. 3 in E Major BWV 1006 (1720)

A portrait of Bach by German baroque painter Elias Gottlob Haussmann.

The period from 1717 to 1723 might have been the happiest of Bach’s professional life. He was employed by Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, a music-loving young monarch who knew what he had in his fine kapellmeister and gave Bach encouragement and freedom that resulted in downright stunning prolificy. Since the Cöthen court was Calvinist, church music was not in the cards; instead, Bach concentrated on secular music, making this the period in which the bulk of his great instrumental works were composed: the Brandenburg Concertos and Orchestral Suites, Well-Tempered Clavier Book One, English Suites, French Suites, and numerous other works that are part and parcel of our musical culture.

Which includes the sonatas and partitas for solo violin, BWV 1001 through 1006, possibly begun before Bach’s Cöthen service but definitely completed in 1720. Nobody is quite sure what violinist Bach had in mind in writing this suites; it could have been himself, but other names have been floated, all of them superlative virtuosos with the technical wherewithal to manage these difficult but rewarding works.

The Prelude from the E Major Partita is familiar and loved, whether in its original incarnation for solo violin or in one of its many later incarnations: Bach himself repurposed it as the opening sinfonia of Cantata 29, and Rachmaninoff gifted posterity with a spectacular arrangement for solo piano, which he recorded in 1933.

Katherine Balch (b. 1991)

Two Songs for Robyn (2020)

We’re all dealing with shutdowns, shelter-in-places, and quarantines.  (Hence this online concert.) Katherine Balch, recent Young American Composer-in-Residence of the California Symphony, created Two Songs for Robyn our of her experiences in shelter-in-place, first in her New York apartment from March to June 2020, and then the sounds outside her husband’s parents’ home in the Colorado Rockies from June to August 2020.

(Hence this online concert.) Katherine Balch, recent Young American Composer-in-Residence of the California Symphony, created Two Songs for Robyn our of her experiences in shelter-in-place, first in her New York apartment from March to June 2020, and then the sounds outside her husband’s parents’ home in the Colorado Rockies from June to August 2020.

These are short works for violin and ‘fixed media’ — what in the old days was ‘tape’ but nowadays consists of digital files. Apartment sounds combines certain street sounds of New York (particularly the tinkling of glass and distant sirens) with a sober, slow-moving violin part, mostly pizzicato—i.e., plucking rather than bowing the strings. Riverwalk opens with the squeak of a screen door to the accompaniment of distant running water that grows progressively more present and eventually erupts in a rush, before subsiding back into its initial calm.

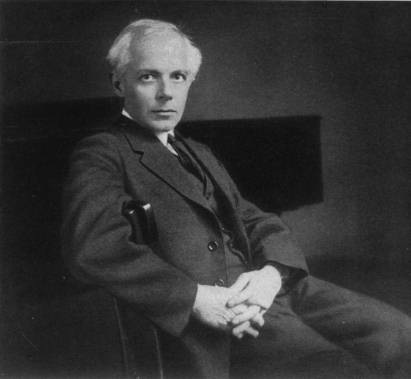

Béla Bartók (1881–1945)

Sonata for Solo Violin (1944)

Béla Bartók in 1927

He was not a well man. Nor was he a happy one. Béla Bartók’s homeland Hungary had thrown in its lot with the Axis powers, and in response the resolutely anti-fascist artist had reluctantly emigrated to the United States in 1940, where he and his family lived on a shoestring in New York City amidst a culture that showed little interest in his music.

And he was suffering from leukemia, which would kill him in 1945 at age 64. But a few rays of light shone through the gloom, such as conductor Serge Koussevitzy’s commission for a large orchestral work that resulted in the beloved Concerto for Orchestra. In 1944, with his illness intensifying, Bartók received a commission from friend and colleague Yehudi Menuhin (a Bay Area native, by the way) for a sonata for solo violin; Menuhin gave the work its premiere in November of 1944.

It’s a four-movement sonata that teems with Bartók’s signature blend of native Hungarian folk styles with a gentle but unmistakable modernism. (It’s odd to think that Bartók’s music was once thought of as forbiddingly cerebral and hyper-modernist; heard at a temporal distance, and in context, it’s clear that he was essentially a late Romantic blessed with a vivid harmonic and melodic imagination.) A worthwhile descendant of Bach’s magnificent solo violin works, the Bartók sonata exploits the instrument to its fullest while creating near-orchestral sonorities via a mere four strings.

Claude Arrieu (1903-1990)

Quintette en Ut (1952)

A product of the same French artistic and educational hothouse that produced a bevy of important 20th-century French composers, Louise Marie Simon studied with such notables as Paul Dukas and Jean Roger-Ducasse before launching into her distinguished and prolific compositional career under the pseudonym Claude Arrieu.

She wrote music of all kinds for all kinds of venues: theater, film, radio, music hall, concert hall, all of it finely crafted, intelligent, and emotionally stable. Her Quintette en Ut (i.e., Quintet in C) for flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon dates from 1952. The work opens with a chipper, jaunty movement that savors of Francis Poulenc at his most boulevardier mode; a steady ‘walking bass’ bassoon line introduces an ambling yet amiable second movement. In third place comes a bit of gentle comedy via a zippy little waltz, then follows a sweetly lyrical fourth movement. The Quintette ends in an effervescent romp shot through with witty interjections.

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the California Symphony’s ground-breaking music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

Second Saturdays @ California Symphony continues in October with a program featuring violinist Robyn Bollinger and California Symphony Wind Quintet. Join us on Saturday, Oct. 10 for Virtuoso Vibrations, FREE to watch online from the comfort of your couch. Learn more here.

Second Saturdays @ California Symphony continues in October with a program featuring violinist Robyn Bollinger and California Symphony Wind Quintet. Join us on Saturday, Oct. 10 for Virtuoso Vibrations, FREE to watch online from the comfort of your couch. Learn more here.