Juan Pablo Contreras (b. 1987)

MeChicano (2022)

Juan Pablo Contreras joins a distinguished line of Mexican-born composers who have brought their sensibilities to concert audiences everywhere: consider Carlos Chavez, Silvestre Revueltas, Manuel Ponce, Arturo Marquez, and Gabriela Ortiz, and many others. Contreras brings his own particular approach to fusing Mexican folk music with the Western classical tradition, and along the way he has amassed an impressive list of honors for a composer who is yet in his thirties, among them a nomination for a Grammy award, performances by 30 major orchestras, a record deal with Universal Music, and the BMI William Schuman Prize.

Contreras tells us that “MeChicano (a combination of Mexican and Chicano) …is a celebration of Mexican American communities that have flourished in the U.S., particularly honoring those in Las Vegas, Fresno, Tucson, Louisiana, Richmond, and Walnut Creek, cities whose orchestras co-commissioned MeChicano.

“In the 1980s, when Mexican Americans became prominent in the U.S., music was one of the artforms that allowed these communities to forge an identity and find a sense of pride and belonging. Mexican American orquestas (a dance-band that synthesized Mexican and American styles) were formed and frequently played live on Saturday Night Dances for their communities. By doing so, they developed a new musical sound that blended traditional Mexican music with American genres such as rock and roll, jazz, and R&B.”

Contreras’s description makes it clear that MeChicano celebrates the two-way fusion between Mexico and America: Mexican folk music is brought to America, but American pop styles filter back into the music of Mexican American communities. All of this is of course framed within the context of Contreras’s own idiom; MeChicano isn’t simply a mashup of various pop and folk styles. Contreras—a new United States citizen after 15 years residency here—suggests that we “think Selena meets Ritchie Valens meets Los Tigres del Norte meets Contreras.”

Wynton Marsalis (b. 1961)

Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orchestra (2015)

Even a casual look through the stories of the great violin concertos reveals that many of them were the result of close collaborations between composer and soloist. Thus it has been with composer Wynton Marsalis and Scottish violinist Nicola Benedetti. Marsalis might be best known as a world-class jazz musician, but he is also a Pulitzer Prize-winning composer who writes in a broad variety of styles. His collaboration with Benedetti proceeded via a back-and-forth flow of communication, sometimes via transatlantic phone lines. (The documentary made about their process is a must-see.)

The result is abundantly and gloriously worth it. The concerto sweeps across American musical styles in a stunning integration of cultures, from Hollywood romanticism to jazz to country to bluegrass to urban bling. That could be a description of an undisciplined hodgepodge, but it isn’t: Marsalis wrote with scrupulous care and integrity. Benedetti speaks lovingly of the new concerto: “Wynton’s concerto has revealed more and more and more to me in terms of the ingenuity of how it is constructed.”

The opening Rhapsody, almost an entire concerto in itself, opens in a dreamtime that veers off into nightmare then back again. The Rondo Burlesque second movement savors of an almost frenetic jazz atmosphere as it bounces off its own walls before settling into an extended solo violin cadenza. Then come the Blues, that quintessentially American genre of heartbreak and regret, here blended with a touch of film noir. To conclude, an appropriately rowdy Hootenanny that even calls on the performers to stamp their feet. (Listeners are advised to refrain, however.) The ending is surprising and wistful: no slam-dunk, blow-the-house-down sendoff, but a fading away into the distance.

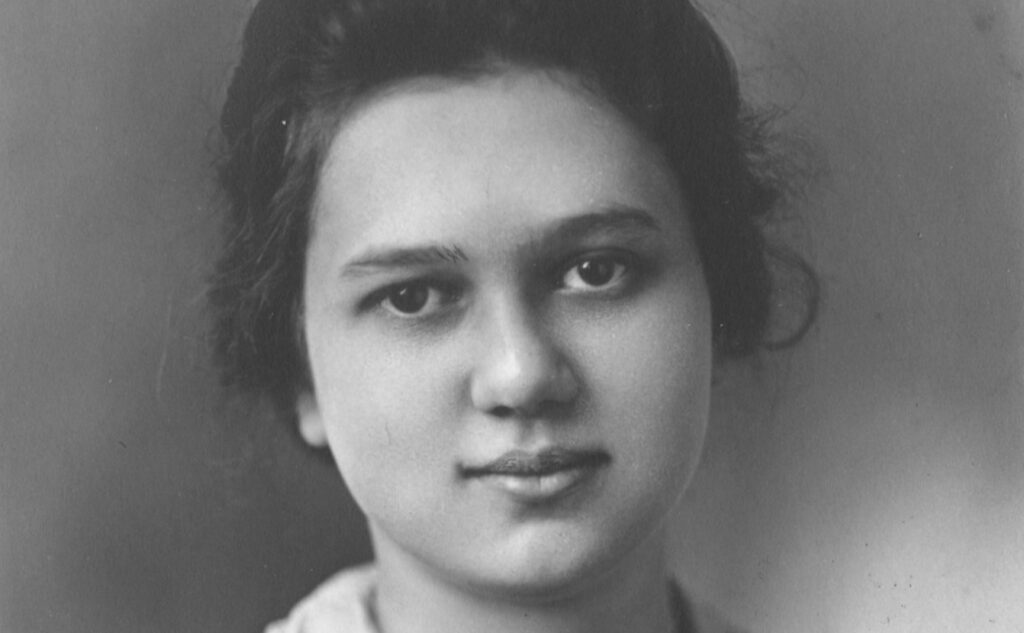

Ruth Crawford Seeger

Rissolty Rossolty (1939)

Ruth Crawford Seeger (née Ruth Porter Crawford) remains a relatively unknown voice in 20th century American music. Part of that has to do with the brevity of her active compositional career: she married Charles Seeger in 1931 and focused her energies on a family that was eventually to include seven children. But another important factor was the Great Depression of the 1930s, during which she came to doubt the validity of modernist music. As a result, from the mid-1930s onward she dedicated herself to collecting folk songs and teaching music in private schools.

Commissioned for a CBS radio program devoted to American folk music, Rissolty Rossolty eventually juggles no fewer than three tunes—one of which is “Rissolty Rossolty”—that Crawford Seeger had gleaned from her folk song collections.

Nota bene: the tune “Rissolty Rossolty”might give cinema buffs a jolt of recognition. It’s the song the Bodega Bay children are singing as the crows gather ominously in the schoolyard in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds.

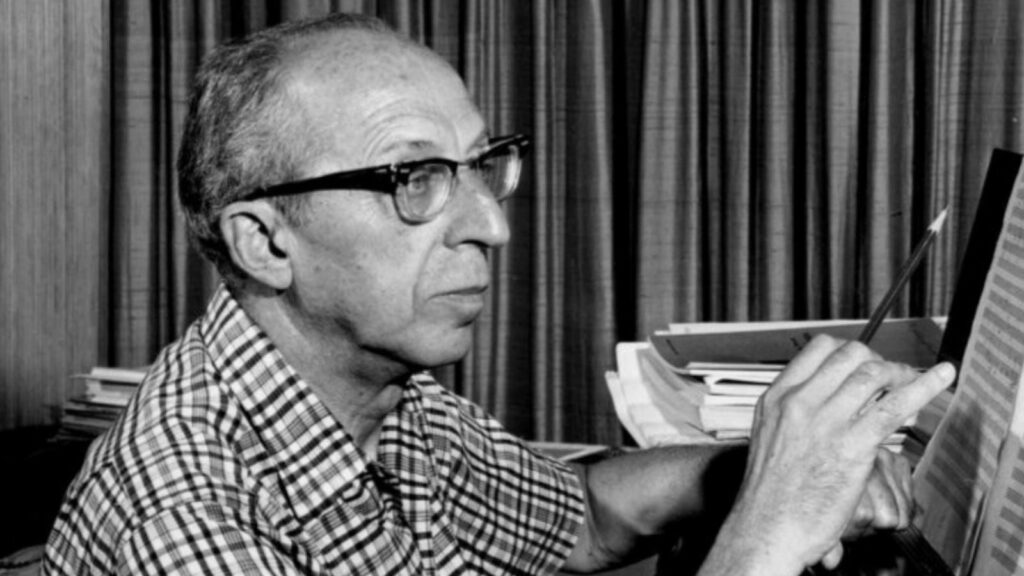

Aaron Copland (1900–1990)

Appalachian Spring Suite (1944/1945)

Irony: a musical idiom indelibly associated with the United States is that of the Jewish son of Eastern European immigrants who received the bulk of his musical education in France. But that’s America for you. Aaron Copland’s compositional career is sometimes described as bifurcated, in that he wrote “modernist” works that were of interest primarily to cognoscenti and “populist” works that quickly became part of the very fabric of American music. That tidy distinction, like so many music-appreciation bromides, blurs upon closer inspection. Copland did not write in two separate styles; rather, he was the possessor of a single, vivid musical language that he could tailor to the situation at hand.

Written on a commission from dancer-choreographer Martha Graham, Copland’s Pulitzer Prize-winning ballet Appalachian Spring wraps folk-inspired melodies, energetic dances, and evocative landscapes into a sophisticated modern package, the whole trimmed and buffed to a wiry yet colorful idiom. The original scoring is for a chamber ensemble of 13 instruments; in 1945 Copland created the slightly abridged orchestral suite by which the work is now best known.

In keeping with the bucolic Americanism that characterized the arts of the WWII era—think Rodgers and Hammerstein’s 1943 Oklahoma!—the ballet tells the story of a rural Pennsylvania community’s building of a farmhouse, centering on a young newlywed couple. Copland’s variations on the Shaker tune “Simple Gifts” might be the best-known part of the work, but from the muted dawn of its opening to its hushed prayerful conclusion, Appalachian Spring truly merits its status as one of the seminal creations of modern American music.

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the California Symphony’s ground-breaking music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

The 23-24 TRAILBLAZERS Season opens with COPLAND—AMERICAN TRADITIONS, featuring violinist Kelly Hall-Tompkins in Wynton Marsalis’ Violin Concerto in D, as well as the consortium premiere of Juan Pablo Contreras’ “Me Chicano”, takes place Saturday, September 30 at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday, October 1 at 4 p.m. at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek. Tickets are $45 to $90 and $20 for students 25 and under, and include a free 30-minute pre-concert talk starting one hour before the performance. Buy tickets online or call or visit the Lesher Center Ticket Office at 925.943.7469, Wed – Sun, 12:00 noon to 6:00 p.m.