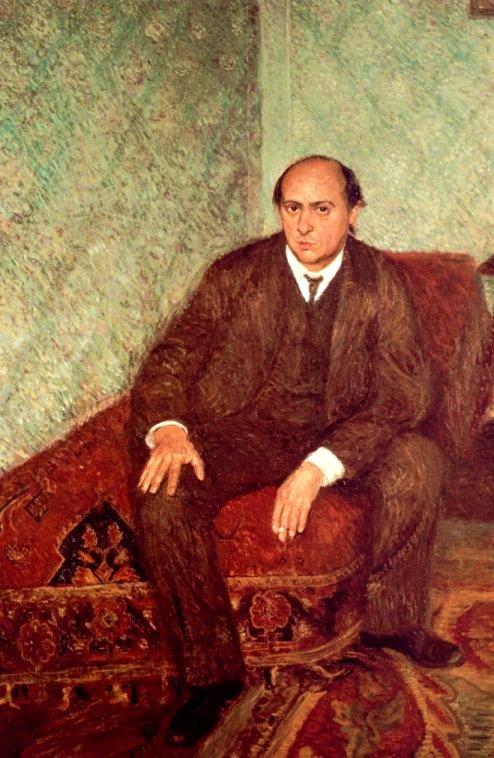

Arnold Schoenberg (1874—1951)

Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night)—Version for String Orchestra

Arnold Schoenberg, painted by Richard Gerstl in 1906 (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

It opens with a cliché: your basic dark and stormy night. A couple is walking through the forest. The woman has a secret to impart to her new lover: she is pregnant, and not by him. He is, not surprisingly, taken aback by this news; she wonders if she has just destroyed their relationship with an indiscretion that happened before they had met.

But he not only forgives her but accepts the idea of the child. You have transfused me with splendor, he says, you have made a child of me. The couple walks on, but the dark and stormy night is no more. Now it has become the high, bright night—transfigured (verklärte) by acceptance and forgiveness.

The story comes from German poet Richard Dehmel, who had suffered a goodly share of brickbats thrown his way via his poetry collection Woman and World, first denounced as obscene then burned by court order. That didn’t stop any number of composers setting his poems—the list includes Richard Strauss, Max Reger, Carl Orff, Kurt Weill, and Alexander von Zemlinsky. Arnold Schoenberg didn’t actually set the text of Dehmel’s Verklärte Nacht; instead, he used it as a springboard for a purely instrumental work, taking its inspiration from the five stanzas of Dehmel’s poem.

A quick heads-up is in order here. This is a very early work of Schoenberg’s, written well before his embrace of abstract expressionism, atonality, and his development of the 12-tone system. It is written in a rich late Romantic tonal language, rich enough to elicit consternation, together with hisses and gasps, at its 1902 premiere and for a good time thereafter. Such a reception is virtually unthinkable nowadays, when Verklärte Nacht is the one Schoenberg work that enjoys general success beyond afficionados of modernism. Clearly, its tonal language is the direct inheritor of both Brahms and Wagner; it is highly reminiscent of Tristan und Isolde, in fact. It is the work of a young man (Schoenberg was 25 at the time), written in a white heat of inspiration (three weeks total.) His original version was for string sextet, but it’s his later 1924 version for string orchestra that is most often heard.

Schoenberg observed in 1937 that “as long as an audience is inclined not to like a piece of music, it does not matter whether there happen to be, besides some more or less rough parts, also smooth or even sweet ones. And so the first performance of my Verklärte Nacht ended in a riot and in actual fights.” But one person who truly loved the work from its inception was Richard Dehmel himself, who after the Vienna premiere wrote to Schoenberg: “I had intended to follow the motives of my text in your composition, but soon forgot to do so, I was so enthralled by the music.”

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the California Symphony’s ground-breaking music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

This is the second episode of Poetry in Motion, a three-part season finale series, premiering FREE online at and on Walnut Creek Public Access TV over three consecutive Saturdays, May 8, 15 and 22. Filmed at Bay Area landmark the Oakland Scottish Rite Center, each 20- to 45-minute episode features music for string orchestra that uses poetry as a source of inspiration.