Thomas Adès (b. 1971)

Three Studies from Couperin (2006)

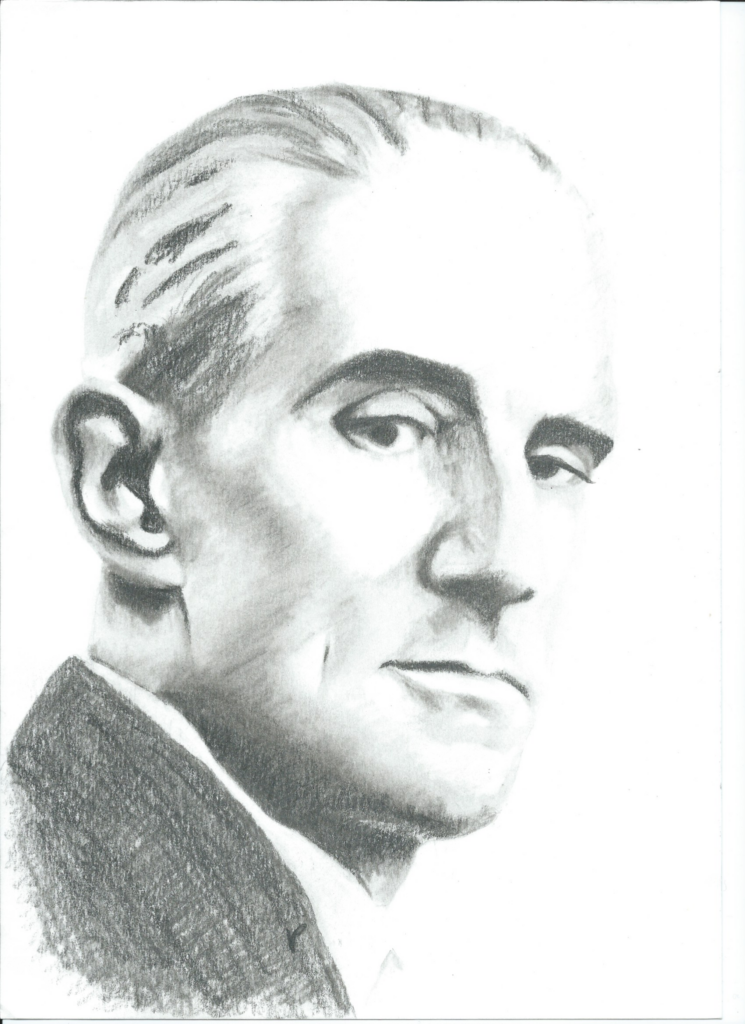

Thomas Adès loathed ‘sports days’—i.e., gym class—in school. (It’s a rare musician who can’t relate to that.) “I’d invent phantom tummy aches and stay at home and listen to records,” he recalls. Those records, collected by his poet/translator father, ranged from folk music to Stravinsky, and as such played important roles in this wide-ranging musician’s development. Adès is a triple threat: composer, pianist, and conductor, he revels in a career that allows him ample space to expand, explore, and grow. With a surprisingly large catalog that includes operas, ballets, chamber, orchestral, and solo works, Adès is as wide-ranging a composer as he is a musician. (And he’s barely past fifty.)

Matt Jolly, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Composed in 2006 for the Basel Chamber Orchestra, each of the Three Studies from Couperin follows precisely the same layout, almost to the last jot and tittle, as the original by Bach’s contemporary François Couperin. Thus one might conclude that these aren’t ‘studies’ so much as ‘arrangements.’ But that would be mistaken; Adès may not omit or change anything, but he adds a cornucopia of ideas that complement and enhance their source keyboard pieces rather than merely arranging them for orchestra.

Katherine Balch (b. 1991)

Illuminate, for Three Voices and Orchestra (2020) (World Premiere)

“A libretto that depicts many shades of femininity,” writes Katherine Balch of her new song cycle Illuminate, “or at least, resonates with my own associations and experiences of this term/idea.” Balch has assembled texts from four of her favorite female poets— Sharon Olds, Adrienne Rich, Alejandra Pizarnik, and Sappho via Anne Carson’s translations, interweaving them with lines from a fifth, seemingly-improbable, source: Arthur Rimbaud’s Les Illuminations. “One of the reasons Rimbaud’s poetry resonates with me is that there are always these seemingly offhanded but critical references to the perspectives of women and children throughout his work,” says Balch. “It’s almost as if he is describing the world through their lens.”

Think of Illuminate as a celebration of friendship, an expression of joy in the unique perspectives of the poets as well as the performers. But don’t expect a straightforward setting of the texts; rather, the lines are broken apart, or sung in special ways, stretched out, or combined in various ways within a lavish orchestral texture that includes a varied array of percussion instruments played with an equally varied array of techniques. (Even the vocalists get involved.) Over the course of five movements, Illuminate explores its themes via a framework of the cycle of the seasons, beginning and ending with the spring.

“I hope the piece will be heard as a joyful outpouring,” writes Balch, “because that’s what I feel when I think about these texts, the women they represent to me, and the women who will be singing them.”

Claude Debussy (1862–1918)

Danse (1890), orchestrated by Maurice Ravel (1922)

Danse presents listeners with a partnership between the two major figures of early 20th-century French music, Debussy and Ravel—so firmly linked in the popular consciousness that one sometimes hears of a composer named Debussyandravel. In actuality they were completely different animals: Debussy ever the avant-garde radical who never met an applecart he didn’t want to topple, Ravel the fastidious conservative with a penchant for channeling the music of the past.

For Ravel, dipping into some Debussy piano pieces from thirty years previously was both an homage to a master that he deeply admired (whatever his occasional statements to the contrary) and also a chance to bring some lesser-known repertory to a wider audience. Among those pieces was the Tarantelle styrienne of 1890, a lively little number that elicits thoughts of Italy via the peasant dance all about exercising out the venom from a tarantula bite. Ravel’s practice of orchestrating his own piano works stood him in good stead as he applied his supreme skill to this charming trifle that is as popular today as it was at its Paris premiere in 1923.

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

Ma Mère l’Oye (Mother Goose) with Prélude and Danse du rouet (1910–11)

Many of Ravel’s orchestral compositions began as works for solo piano. In some cases the originals have remained dominant in the repertory, but in others it’s his transcriptions for orchestra that have established themselves so well that they’ve almost obliterated their keyboard originals.

That appears to be the case with Ma Mère l’Oye, which Ravel originally wrote for the gloriously gifted Mimi and Jean Godebski—ages 6 and 7—as a piano duet. Naturally, Ravel kept the lid on technical challenges, which correspondingly inhibited the production of unusual or varied sounds from the piano. (Although less than you might think.) Publisher Jacques Durand persuaded Ravel to orchestrate the pieces, which he did with his usual scrupulous attention to detail and nuance, while simultaneously retaining their original clarity, modesty, and small-scale ambition. He even went on to expand the suite into a ballet score, but it’s the shorter, more intimate suite that has become a beloved orchestral staple.

Inspired by seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French collections, especially Charles Perrault’s Contes de ma Mère l’Oye of 1697, Ravel’s suite brings familiar and unfamiliar tales to musical life. After an introductory Prélude, Sleeping Beauty has pricked her finger on the spinning wheel (Danse du rouet, or ‘spinning wheel dance’) and lapses into a deep slumber for Pavane of Sleeping Beauty, followed by a portrait of tiny, valiant Tom Thumb. Laideronnette, Empress of the Pagodas takes the somber tale of “The Green Serpent” on a whimsical fantasy with sparkling chinoiserie reminiscent of 18th-century painter François Boucher’s delicate Chinese style. It’s followed by a “conversation” between Beauty and the Beast—characters well known to just about everybody by now—then concludes with a ‘happily ever after’ as a princess is awakened by her prince charming in an appropriately enchanted garden.

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the California Symphony’s ground-breaking music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

The California Symphony’s FRENCH IMPRESSIONS featuring previous California Symphony Young Composer in Residence, Katherine Balch takes place Saturday, March 26 at 7:30 PM and Sunday, March 27 at 4 PM at the Lesher Center for the Arts. Tickets are $44 to $74. Buy tickets online or call or visit the Lesher Center Ticket Office at 925.943.7469, Wed – Sun, 12:00 noon to 6:00 pm.