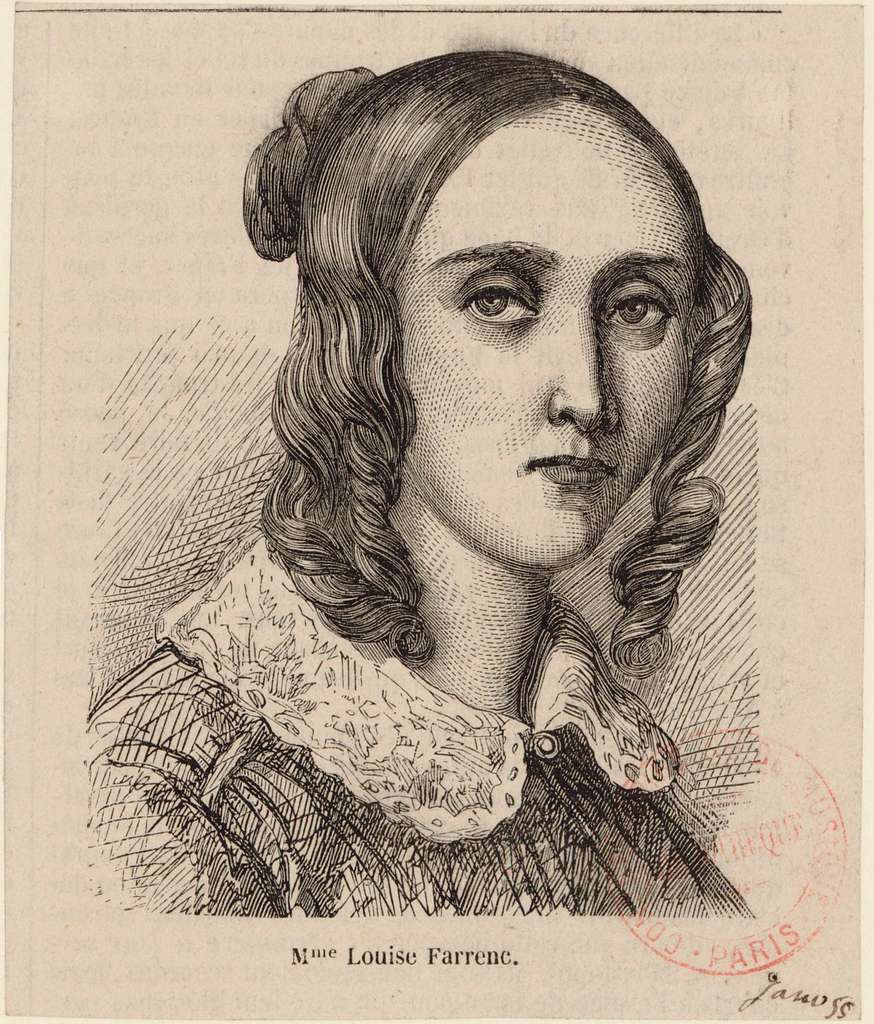

Louise Farrenc (1804–1875)

Overture No. 2 in E-flat Major, Op. 24 (1834)

Isabelle Vengerova. Rosina Lhevinne. Adele Marcus. Yvonne Loriod. All major-league piano teachers at major-league conservatories, and all women. They shared an unheralded predecessor in 19th century composer and pianist Louise Farrenc, mainstay piano faculty at the Paris Conservatoire for decades. She concertized in prestigious venues. Her compositions were played by headliners such as Joseph Joachim.

As a composer she was of a distinctly conservative stripe, eschewing excess and any hint of glitz. Her catalog runs to the traditional genres: chamber music, symphonies, and (understandably) lots of solo piano stuff. After her death in 1875 she, and her music, fell into obscurity, and that’s a pity. She left a considerable legacy, well worth reviving. Consider her Overture No. 2 in E-flat Major, Op. 24 of 1834: bold, dramatic, and exuberant, it demonstrates Farrenc’s firm command of the orchestra and her skill in writing compositions that engage, entertain, and inspire.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125 (1824)

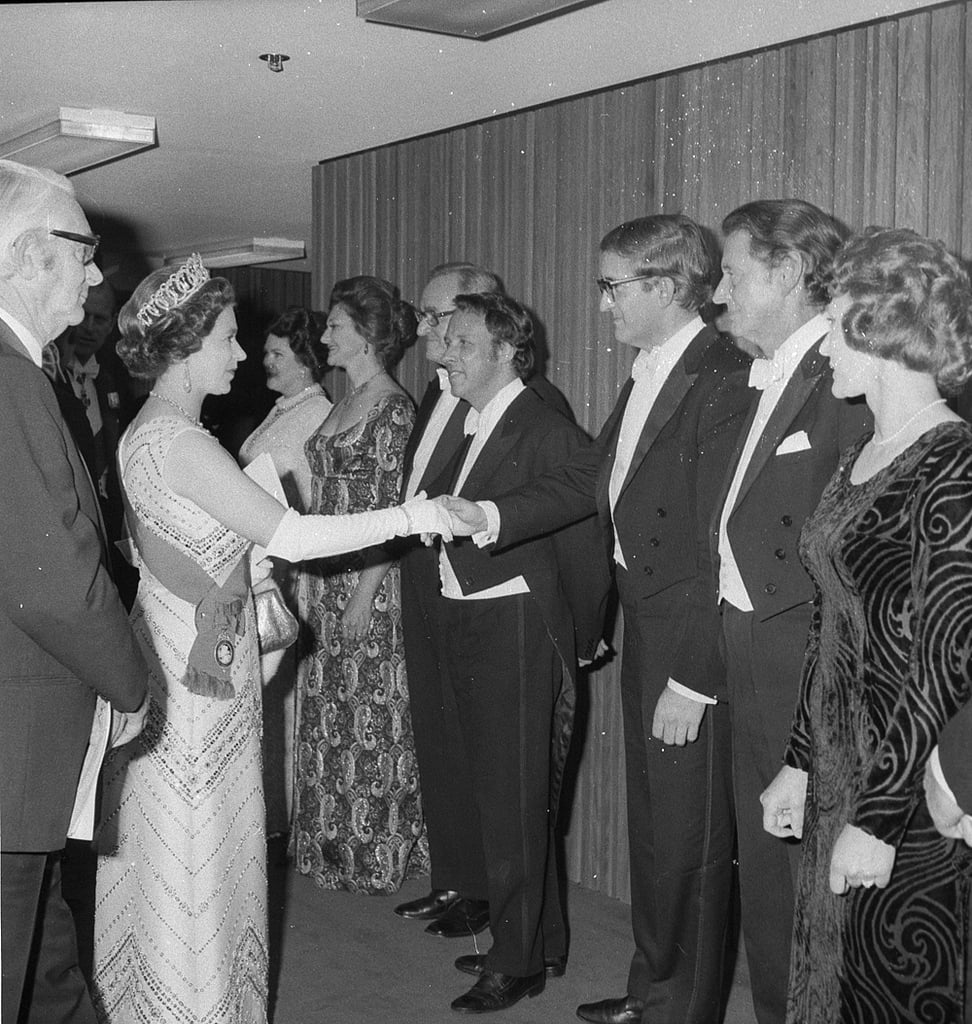

It extended for 96 miles. It stood for 10,316 days. Then in 1989 the Berlin Wall finally came down. The physical barrier itself required about two months to remove, but the emotional one required far longer—if, indeed, it is altogether gone yet.

Only one musical composition could celebrate the unification of the German people: Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with its unquenchable message of optimism in the face of adversity.

On March 10, 1824 Beethoven offered the publisher Schott “a new grand symphony, which ends with a finale (in the style of my piano fantasy with chorus, but far greater in content) with solos, and chorus of singing voices, the words from Schiller’s immortal well-known Lied: To Joy.” The great symphony had its premiere a few months later, on May 7 at Vienna’s Kärntnertor Theater.

Here a bit of explanation on symphonic performance in the early 19th century is in order. Although it was common for orchestras to have a conductor in the modern sense, most of the heavy lifting of leading the ensemble was handled by the first violinist—called the ‘concertmaster’ in America or the ‘leader’ in England. The performance was therefore guided by a dual leadership—the leader at first violin and a ‘conductor’ either from a raised podium or just as often from a piano.

Given that Beethoven was almost entirely deaf by 1824, his role in the performance would be of necessity limited; he could easily derail the entire thing with one ill-considered gesture or cue. As it was, he very nearly did, given that he was apparently unaware when the piece actually ended but kept on gesticulating a bit longer. On the whole it didn’t matter. The performance was borderline unhinged anyway, done in by insufficient preparation, copyist errors in the parts, and the unprecedented difficulty and complexity of the work.

It bowled them over anyway. The Ninth was not one of those seminal masterpieces that was initially scorned and then won acceptance gradually; it entered the world with a roar and has remained the king of the symphonic repertory ever since. One can trace the entire history of the Romantic symphony as a succession of composers all trying to come to grips with Beethoven in general and the Ninth in particular. It was the ultimate, the ideal, the unmatchable standard against which any and all would be measured and found wanting.

What is it about the Ninth that warrants such a stratospheric reputation? Part of the answer is easy enough: it was longer than any symphony yet written, it required larger forces, it demanded more out of those forces, and then there was that matter of a gargantuan finale requiring full chorus and quartet of vocal soloists.

Even more important is its palpable sense of victory, in Beethoven’s day understood as the ultimate European victory over Napoleon—who, we should remember, had laid siege twice to Vienna during his career—but afterwards coming to stand for the triumph of will, love, and optimism against adversity. Therefore it is a symphony that means something beyond the notes on its many pages. And for many, that meaning is wrapped up in a hope, or even a certainty, in a future that will be better, that the human spirit will win out in the end, that if we just believe in ourselves enough, present difficulties will give way to future happiness.

Over the course of the Ninth’s 70-odd minutes, Beethoven takes us on a journey through human existence itself. The symphony commences with sonorities so elemental that they would have been familiar to our cave-dwelling ancestors, then expands into a magisterial expression of human civilization at its highest levels, via a grand structure that is the musical counterpart of a soaring cathedral. Strife and battle are covered in the propulsive, surging second movement, while the lyrical heart of the work lies in its imperishably expressive slow movement, a place where time slows and we are consoled in an embrace of luminous compassion.

And then, the colossal finale, itself as long as many earlier symphonies, a multi-sectioned affair that mixes operatic recitative (and not always sung, either), aria, chorus, variation, and a mighty symphonic form blended with Schiller’s “Ode to Joy.” Be embraced, you millions! The kiss is for the whole world! Brothers, above the canopy of stars must dwell a loving father.

Joseph Haydn ends his glorious oratorio The Creation with Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, still innocent, still clad ‘in native worth.’ But Beethoven ends the Ninth not on Earth but with a titanic embrace of the very heavens: Joy!! Beautiful spark of divinity! Divinity! We are all blessed with the divine spark, he says: it is our universal, imperishable and eternal birthright. All we have to do is claim it.

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the California Symphony’s ground-breaking music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

The 24-25 CROWNING ACHIEVEMENTS Season beings with BEETHOVEN’S NINTH, on Saturday, September 21 at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday, September 22 at 4 p.m. at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek. Single tickets start at $50 and at $25 for students 25 and under, and include a free 30-minute pre-concert talk starting one hour before the performance. Buy tickets online or call or visit the Lesher Center Ticket Office at 925.943.7469, Wed – Sun, 12:00 noon to 6:00 p.m.