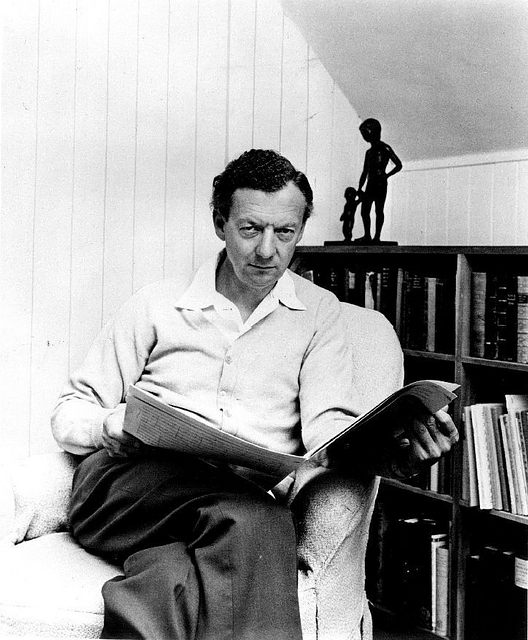

Benjamin Britten (1913–1976)

The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, Op. 34 (1945)

Compositions that teach the instruments of the orchestra make up a lively sub-genre of the literature, including beloved mainstays as Camille Saint-Saëns’s Carnival of the Animalsand Serge Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf. Benjamin Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra stands tall amongst those, not only for its pedagogical worth, but also for its superlative musical content.

To fulfill a commission for the British documentary film Instruments of the Orchestra, Britten fashioned a set of orchestral variations on a theme from Restoration master Henry Purcell’s 1695 incidental music for Aphra Behn’s tragic play Abdelazer. (The play flopped, but Purcell’s music went on to great things.)

Britten’s Guide is meticulously structured, exquisitely paced, and magnificently orchestrated. After a grand statement of the Purcell theme in full orchestra, Britten takes us through 13 variations, each highlighting specific instruments. The wind instruments start it out with four variations for flutes/piccolos, oboes, clarinets, and bassoons. The strings follow with four variations of their own—violins, violas, cellos, and basses. The harp provides a brief interlude, then it’s time for the brass—horns, trumpets, trombones and tube, after which the percussion takes charge in a glittering display of timpani, bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, triangle, snare drum, woodblock, xylophone, castanets, tam-tam, and whip.

Perhaps it could have ended there, but instead Britten brings it home in an utterly dazzling finale. It’s a fugue, a game of musical follow-the-leader based on an effervescent tune that in its many repetitions recaps the instrumentation heard earlier—four winds, four strings, harp, four brass, and percussion—before the Purcell theme re-enters in full orchestral glory, bringing this spectacular orchestral fantasy to a blazing close.

Mason Bates (b. 1977)

Philharmonia Fantastique (2021)

Grammy-award winning Mason Bates isn’t the only creator of Philharmonia Fantastique; he is joined by director/sound designer Gary Rydstrom and animation director Jim Capobianco. From which we may conclude that Philharmonia Fantastique is more than a musical composition. It’s something new: a concerto for orchestra and animated film.

Not your usual teach-the-orchestra affair, in other words. In fact, it’s so much of our own time and ethos that it has its own web page, from which we learn about a magical animated Sprite that guides us, as “we see violin strings vibrate, brass valves slice air, and drumheads resonate.” The site concludes that by “imaginatively blending traditional and modern animation styles, it is a kinetic and cutting edge guide to the orchestra. By the film’s end, the orchestra overcomes its differences to demonstrate ‘unity from diversity’ in a spectacular finale.” Even though Britten’s Young Person’s Guide was written for a film, that work is most often heard alone as an orchestral composition. That won’t do for Philharmonia Fantastique. The animated film itself is an integral component, and not merely a visual enhancement along the lines of those unforgettable animations in Disney’s Fantasia or its ilk. Thus Philharmonia Fantastique can be understood as the continuation of a long tradition of orchestra-teaching compositions, now brought into the 21st century as a multi-media experience that promises to display the glories of the modern orchestra with an unprecedented level of engagement.

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Symphony No. 4 in E Minor, Opus 98 (1885)

“New and original and yet authentic Brahms from A to Z,” wrote the young Richard Strauss to his father shortly after the work’s premiere in October 1885 by the court orchestra of Meiningen under the direction of Hans von Bülow. “I had the feeling that I was being given a beating by two incredibly intelligent people,” said critic Eduard Hanslick of the first movement after hearing Brahms and Ignaz Brüll play through the work privately on two pianos.

It had taken Brahms over two decades of abandoning, re-purposing, re-writing, and striving to break through with his First Symphony of 1876. In so doing he had breathed new life into a genre considered moribund and opened the door to a veritable Renaissance of symphonic writing from composers as varied as Antonín Dvořák, Anton Bruckner, and Gustav Mahler. He had also cleared a path for himself, as his Second Symphony followed a year after the First, in 1877. The Third premiered in 1883 and was proclaimed as Brahms’s Eroica by no less than conductor Hans Richter.

Then came the Fourth, which Brahms wrote from 1884 to 1885 and gave a trial premiere in Meiningen. The public grabbed on to the work immediately, but some of Brahms’s closest circle were less convinced. It seemed so stern, so unremitting, so far removed from the moral uplift typical of Classical symphonies, an uplift that Brahms had often echoed in his own works. Here was a symphony beginning in the minor mode but that shunned the usual journey into major, dark to light, night to day. It ended as it began, in E Minor. The Brahms Fourth has an overriding quality or color—what Verdi called the ‘tinta’ in his operas—of melancholy, an autumnal gold.

It is also amongst Brahms’s most rigorously structured works, built out of a few basic intervals and employing for its last movement the then-obsolete form known as passacaglia—a steadily recurring bass line that provides a foundation for a series of variations. And yet it is also a deeply loveable work, not only due to its sweeping first movement, the exquisite yearning of its slow movement, or the fiery exultation of the third-place scherzo in C Major, but also for its lyricism, its depth, and the aura of inevitability that arises from its superlative structure. Incomparably rich, sweeping and majestic, the Brahms Fourth “is not a work that unlocks its secrets easily,” according to Walter Frisch. Eduard Hanslick would agree with that analysis: so taken aback by the symphony at his first encounter, he eventually claimed it to be “like a dark well; the longer we look into it, the more brightly the stars shine back.”

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the California Symphony’s ground-breaking music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

The 24-25 CROWNING ACHIEVEMENTS Season continues with BRAHMS ODYSSEY, on Saturday, November 2 at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday, November 3 at 4 p.m. at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek. Single tickets start at $50 and at $25 for students 25 and under, and include a free 30-minute pre-concert talk starting one hour before the performance. Buy tickets online or call or visit the Lesher Center Ticket Office at 925.943.7469, Wed – Sun, 12:00 noon to 6:00 p.m.